- Home

- Laurence Yep

Isabelle in the City

Isabelle in the City Read online

This story is dedicated to “Uncle Sam” Sebesta.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1: In Miki’s Shoes

Chapter 2: Paper Dresses

Chapter 3: The Shopping Trip

Chapter 4: Dancing on Doors

Chapter 5: Jade’s Great Idea

Chapter 6: Sharing the Dance

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Paper Art Glossary

Paper Fashions

Preview of Gabriela

Copyright

When I came to New York, I didn’t expect to see Africa and Australia, too. But every morning when I woke up and looked over at the window, I saw tiny origami elephants and giraffes strolling across the windowsill, and kangaroos hopping away from crocodiles on the desktop beneath the window. Horses, frogs, butterflies, and pretty much every other animal filled my roommate’s half of our room.

Miki had made the animals in just six days. No piece of paper was safe from her fingers. By the end of a meal in the cafeteria, she had turned paper napkins into a little menagerie around her plate.

Miki was ten, like me, but she’d come all the way from Japan to take the summer intensives at the Knickerbocker Ballet Company, or the KBC, here in New York City. My big sister, Jade, and I had come from not quite so far away: Washington, D.C., where we both studied ballet at the Anna Hart School of the Arts.

Being at the KBC this summer felt like a dream come true. For five weeks, I would be surrounded twenty-four hours a day by two hundred girls and boys who loved dancing as much as I did! The only problem? My new roommate and I weren’t exactly hitting it off.

I was bursting with questions about Miki’s life in Japan, but for the past six days, I’d felt as if there were this wall between us. And Miki hid behind it, busy with her origami or her video games.

So on Friday morning, I asked her, “Miki, could you teach me how to make any of those?” I swept my arm in an arc to indicate her origami zoo.

Miki hesitated, her eyes flicking from side to side. “Do you have paper?”

“I have some cafeteria napkins.” I waved several tan squares at her.

She shook her head. “Napkins are too soft. You need good paper.”

I pointed to the windowsill and desk. “But you use napkins sometimes.”

Miki responded slowly, like someone walking carefully over a slippery floor. “I make them to exercise my fingers,” she said. “But you are a beginner. You would learn bad habits with bad paper.”

“Oh,” I mumbled, tucking the napkins into my pocket. “I didn’t realize these were so lousy for origami.”

When Miki opened her mouth, I thought she was going to say more, but instead she began playing her video game.

The light from the screen flickered across her face as her fingers danced over the buttons. She must have been playing on a hard level, too, because she drew her eyebrows together in concentration.

I couldn’t figure Miki out. She didn’t seem to mind sitting with me at meals, but I’d be in the middle of talking to her when she’d take out her game and begin playing. Was I that boring? Worse, was I that annoying?

Back to square one, I sighed to myself.

While packing my bag for my first morning class, I snuck peeks over the heads of Miki’s zoo animals and out our room window. I still wasn’t tired of looking at the view. Washington, D.C., had some pretty tall buildings, but nothing like here in New York.

Below us, the Chelsea neighborhood looked like toy blocks. The gray, red, and brown rectangles and squares were arranged in little groups. On top of some were small cylinders, which I knew were water tanks. Beyond, I saw the blue of the Hudson River and the dark mass of New Jersey.

Along the roof’s edge of the nearest building were stone carvings of women’s faces, covered with vines and leaves. I couldn’t see why the builders had put them all the way on top. No one in that building could see the carvings, and we were in the only building tall enough to look down over them. But then, New York was full of fun puzzles like that.

Tap, tap, ta-tap, tap, tap. Someone rapped out the first six beats of The Nutcracker on our door, and I knew it was my big sister, Jade. At home, we shared the same bedroom, so it still felt a little strange to hear her knock.

“Come in,” I said.

When Jade opened the door, I heard the voices of our floor mates gathering by the elevators. Students came from around the world to take the summer intensives, so I heard snatches of Spanish and something like French and German—and maybe Chinese. But that didn’t seem strange to me. Back home in Washington, D.C., I was used to hearing a lot of different languages, because so many people came from other countries to work there.

Jade was thirteen, two and a half years older than me and tall for her age. But she was still shorter than the rest of the girls on our floor, many of whom were fifteen or older. Her long blonde hair was done up in a bun and she had her dance bag in her hand. She was wearing loose shorts over her leggings and had left her blouse unbuttoned over her light-blue leotard, the ends of the blouse knotted over her stomach.

“Hi, Miki,” she said. “How are things?”

Miki lowered her video game. “What things?”

Jade scratched her cheek. “Um, well … you know, classes. Cafeteria food. My sister’s snoring.”

“Hey!” I objected. “You’re the buzz saw.”

“Not me,” Jade grinned. “Mom says I’m quiet when I sleep, but you take after Dad.”

Miki looked back and forth between us. She couldn’t tell if we were serious or just teasing, and I think it made her uncomfortable. “I have to go to class now,” she said, smoothing her long black hair back into a bun. She grabbed her dance bag, slipped her video-game player into it, and left the room.

As Miki closed the door behind her, Jade said, “I didn’t mean to drive her away. Was it something I said?”

I shrugged. “Who knows? It’s hard to talk with her.”

Jade picked up an origami frog and turned it around in her fingertips. “She might be shy,” she suggested.

I shrugged. “I wish they had put you and me together instead,” I said, zipping up my bag. I always feel like I can handle anything with my big sister around.

“Maybe they wanted us to meet new people,” Jade said, setting down the frog.

I felt a little guilty about that. If I wasn’t hanging out in Jade’s room down the hall, she was keeping me company in mine. My big sister was looking out for me, as usual. She was making sure that I didn’t feel too lonely or homesick. “I guess it’s hard for you to make new friends with me tagging along,” I said, glancing sideways at Jade.

She gave me a reassuring smile. “You’re all the company I need,” she said firmly. Jade danced over to the door and opened it. “C’mon, sis. We’d better get to class now.”

The dorm rooms were on the upper floors of the KBC building, with offices on the ground floor and the cafeteria floor between. The elevators were crowded this morning, as usual, but we squeezed into one eventually. When we reached the ground floor, we hurried with the other dancers past the posters from the various shows at the KBC. As we moved together through the revolving door onto the sidewalk, the July heat hit us.

The warmth wasn’t stopping the city, though. Cars and trucks filled the street, waiting for the lights to change, and people hurried along the pavement. Somewhere nearby, a contest for the loudest horn had broken out among a bunch of vehicles.

The KBC studios were in the theater two buildings over, which doesn’t sound like a lot until you realize how w-i-i-i-de those buildings are. By the time we were past the supermarket, the leotard under my T-shirt was already be

ginning to feel damp and clammy. Today New York was just as humid and uncomfortable as D.C. could be in the summer.

Even so, I could feel the excitement growing inside me, so I picked up my pace. I was going to dance again!

When Jade and I had auditioned for the KBC summer intensives, some of my friends thought the program would be like summer camp, but it was so much more. I got to dance the whole day instead of half of it like at my school, Anna Hart. And even though the teachers here covered many of the same movements and steps that my teachers at Anna Hart did, I was still learning a lot.

As Jade and I stepped through the stage door of the theater, I was happy to feel the cool rush of air-conditioning. We joined a stream of students heading toward the rear of the theater, past a guard at a desk. We had to wait for the elevators again, but eventually we got up to the third floor.

I turned right down the hallway while Jade headed left. “To the stars,” I said to her. That was our school motto, which we used to wish each other good luck.

By now, though, Jade was focused on her ballet class, so she just nodded. She stared straight ahead, her mouth a determined line as she moved down the corridor. It was my sister’s “dance face”—just like the “game face” of a basketball player before a big game. But maybe that’s why Jade danced so well: she treated each class as if it were for the championship.

Eagerly, I walked into Studio 301 for my ballet technique class. After dropping my bag in a corner, I took off my T-shirt. I’d worn a short dance skirt, so I had to put on only my ballet slippers to be ready. I began to stretch, impatient to get out on the floor and dance.

Ms. Aloff, our instructor, was a small blonde woman whose energy filled the room. Her hair was tied in a tidy knot at the base of her neck, and bangs fringed her forehead. When she had been a principal dancer at New York City Ballet, the bangs had been her trademark.

Ms. Aloff was not only one of our ballet instructors, but she also was the head of the summer intensives. I felt a flutter of nervousness. I really didn’t want to make mistakes in front of her.

“Good morning, class,” she called. “How are you all getting along together after your first week? Remember, the summer intensives aren’t just about dancing. They’re about the friendships you make, too.”

I paused to think about that. I was holding my own in classes, but I was doing a lousy job of making friends. I’m going to try even harder to get to know Miki better, I told myself.

We started slowly at the barre as we eased into our workout. But soon the piano began tinkling out fast, energetic notes. Ms. Aloff seemed to be all over the room making corrections, and yet her eyes missed nothing. She might be correcting the arm positions of a dancer on one side of the studio, and the next moment she was bouncing—she never walked—over to the opposite wall to help another.

The only student whose form she didn’t correct was Miki. When we were doing tendus, I glimpsed her reflection in the mirror from the corner of my eye. Her toes quickly brushed the floor as she extended her leg out and then back again, so both feet were flat with the heels touching. She did the move so easily, it reminded me of the tail of our cat, Tutu, as it swept back and forth.

The only comment Ms. Aloff made was, “Nice, Miki, but remember to really feel the music, too.”

When she came to me, though, she actually knelt and gripped my foot in both hands. “Arch your toes more, Isabelle, and point your foot here.” She touched the area behind my big toe and then my ankle. “And here.”

Then she stepped back to watch my tendus before she gave a nod. “Keep that up.”

Miki was just as good when we did our center work. Her arabesques were picture-perfect, with her right leg stretched behind her and her arms held out just right. But she got a little tense whenever she tried to leave the ground. Ms. Aloff had to keep reminding Miki to relax her neck and not raise her shoulders when she jumped.

My jumps were the one thing that Ms. Aloff didn’t correct, except for one small suggestion. “Land on your whole foot and not just the ball, Isabelle,” she told me. “That will give you a better push for the next jump.”

I repeated her instructions to myself over and over while I waited for my next turn on the floor. We moved out in a group of four with Miki to my left, and when I landed after my first jump, I made sure my heel was touching the floor with the rest of my foot.

When I pushed off for a second jump, I felt the extra power that sent me soaring. When we reached the wall, I was grinning from ear to ear.

At the end of class, Ms. Aloff thanked us as she usually did and clapped her hands. And, tired but happy, we gave her a round of applause in return.

As I headed over to my bag to get my bottle of water, I grinned at Miki. “Great class.”

She nodded. “Yes, it was.”

That was the longest sentence she spoke to me all the way back to the dorms, no matter how hard I tried to strike up a conversation. So finally, I quit trying.

When the elevator reached our floor, there was a big crowd in front of it. They weren’t trying to get into the elevator. They were just standing around talking excitedly.

Miki and I had managed to wriggle our way into the mob when I bumped into Abby. She was Jade’s roommate, even though she was a couple of years older than Jade. Abby’s brown hair had been twisted into a braid on the side, and she was wearing a green tank top over black shorts.

“What’s going on, Abby?” I asked her.

She grinned and pointed at a poster taped to the wall near the elevators. “Big news, Isabelle. Every year the dorm holds a contest, and each floor decorates its doors. The floor that does the contest theme best usually gets free pizzas and bragging rights, but this year a trustee has donated money, so the winners can go see a performance by New York City Ballet up in Saratoga.”

I gave a little gasp. “Really?” My sister and I had missed NYCB when they’d performed at the Kennedy Center in Washington last spring. Jade had been busy with special ballet lessons, and I’d been rehearsing for a traveling performance at nursing homes and children’s hospitals.

“For this year’s contest, we have to show what the summer intensives mean to us,” Abby explained.

I spun around to look at Miki. “Wouldn’t that be great if we won?”

“Yes,” Miki said. She opened her mouth as if to say more, and I held my breath. I felt like I was watching a trapeze artist about to do a triple somersault in mid-air.

This contest will give me a chance to get to know Miki better, I thought, so I tried to encourage her. “Let’s put on our thinking caps and come up with something amazing.”

She drew her eyebrows together. Was she trying to come up with something?

Suddenly, I realized that it was no use creating an amazing design for the door if we had no materials to decorate it with. At home, I would have found supplies in my mom’s sewing room, where we spent a lot of time together—Mom working on her textile art and me designing costumes for my ballet performances. But I was a long way away from my home, and Miki was even farther from home. What could we use as decorations?

Then I saw the head counselor, Hailey Yagyu. She was a Japanese American from Long Island with a round face and a broad grin.

When Hailey saw Miki, she said something in Japanese to her. Miki broke into a smile—the only time I’d seen her do that—and responded in Japanese.

“Miki says you two are going to decorate your door together,” Hailey said to me.

“That’s right, but we’re going to need to get stuff to do that,” I said.

Hailey asked Miki a question in Japanese, and Miki nodded emphatically.

“I can help you girls with that,” said Hailey. “I remember seeing your names on the field trip to the museum tomorrow, right?” Hailey checked the schedule on her phone. “There’s an art supply shop not too far away from the museum, and a trimming shop, too, I think. Maybe we can make a couple of quick stops before we go on the harbor cruise.”

�

��Could we?” I asked. I could already imagine the treasures the shops would hold. Tomorrow couldn’t get here soon enough!

Back in our dorm room, I tried for the next hour to get Miki to help me think of some door-decorating ideas. All she did was nod her head at my suggestions and then go back to playing her game. I felt a swell of frustration. I was so excited about the contest that I had to talk with someone. So even though I hadn’t wanted to hog my sister’s time, I wound up heading to Jade’s room down the hall.

Just as I was about to knock, the door opened. “Hey, Isabelle,” Abby said. Beside her was Kayti, a tall Australian girl with long black hair. She and Abby had both come to the summer intensives for the last couple of years, so they hung out together. They had their meal cards in their hands.

Beyond them, I saw Jade standing in the center of the room. Was she about to go to eat with them? That made me feel guilty. If I tried to talk to her now, I might keep her from her new friends again.

Abby and Kayti had already stepped past me and were heading to the elevators, but I figured Jade could still catch them. “You go ahead,” I said to my sister. “I just remembered that I forgot something in my room.”

But my sister could always tell when something was bothering me. “I wasn’t going to the cafeteria just yet,” she said. “I’m practicing some steps from class.” Jade waved me inside. “Come on in.”

Maybe she was telling the truth about practicing, or maybe she was making up an excuse so that she could help me yet again. But I accepted her invitation as I always did and plopped down in a chair.

While Jade danced, I looked around. Jade’s half of the room was plain. The only thing taped on the wall was her schedule of classes, and like me, she was using the blanket and sheets the dorm had provided. Even though our parents had driven us and our things up from D.C., we’d packed only the basics on the list the KBC had given us: stuff like shampoo, and leotards and ballet shoes for class.

But an experienced student like Abby had made her side of the room very homey. Decorating the wall were KBC posters and photos of past summer intensives—I recognized younger versions of Abby with other boys and girls. Her bed had a coverlet with red roses and a pillowcase and sheets to match, plus a white teddy bear perched on the pillow. Since Abby had flown in from her home in Seattle, her family must have shipped a lot of this stuff to her.

The Tiger's Apprentice

The Tiger's Apprentice Bravo, Mia

Bravo, Mia STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord

STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord Isabelle in the City

Isabelle in the City Isabelle

Isabelle To the Stars, Isabelle

To the Stars, Isabelle Designs by Isabelle

Designs by Isabelle A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans

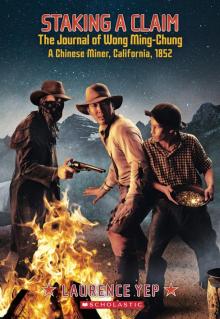

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Staking a Claim

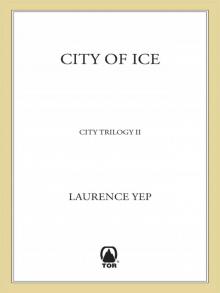

Staking a Claim City of Ice

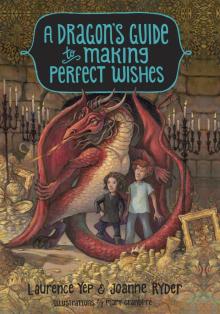

City of Ice A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes

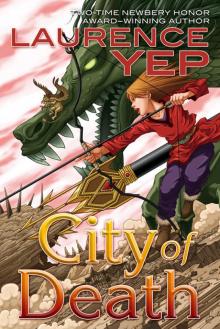

A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes City of Death

City of Death