- Home

- Laurence Yep

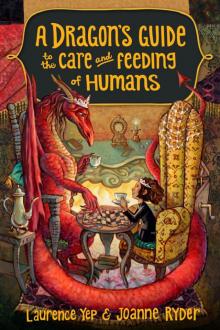

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Page 2

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Read online

Page 2

This Means You, Winnie!

I knew she could read, so if she ignored the sign, I would have to make it clear to her that she was not welcome. A firm paw, after all, is the key to dealing with humans, who are over ninety percent monkey—and there is no paw firmer than mine.

Satisfied, I pinned the sign to the front of the door and tried to put the bothersome little creature out of my mind while I considered my other problem.

The email inviting me to the Enchanters’ Fair had arrived just before Fluffy died. The largest magical festival of the year was now just a couple of days away, and I had to make a decision about whether to take part or not. As I was a founding member of the festival as well as the reigning Queen—a title I earned every year by winning the major magical contest of the Fair—the other magicals would expect me to attend and enter again. They wouldn’t understand why I would mourn for a natural, as we called humans—only my friends would sympathize.

So I decided against making a token appearance, because once I was there, I would be unable to resist competing in the Spelling Bee. Expanding my knowledge of ancient spells was my passion, and I was never averse to a challenge.

I thought of the sorceress who considered herself my greatest rival. “You’ve always wanted to be Queen of the Fair, Silana,” I murmured. “Congratulations.”

I was just typing a polite email to the Fair committee when the door opened and Winnie entered.

I should have known a sign only works for someone with a minimal sense of courtesy.

“I brought some checkers,” she announced, holding up a cardboard box.

I pointed at the front door. “Didn’t you read my sign?” A new thought came to me. “Or can’t you read cursive? Should I have written in block letters?”

“I can read cursive perfectly well—even if you do use too many curlicues,” she said, tracking dirt over the Bokhara again on her way to the dining table. “Great-Aunt Amelia said you like to play games. I’ll even let you cheat.”

I thumped my tail angrily, and when I saw the cloud of dust rising from my carpet, I realized I needed to clean my rooms again. “I do not cheat.”

“Great-Aunt Amelia said you’d say that.” From the box, Winnie took out a piece of folded-up butcher paper. When she spread it on the tabletop, I saw that the squares had been hand-drawn and the border decorated with crude crowns, unicorns, and lions.

“Where did you get that?” I demanded.

“I made it.” She began to take out checkers cut from cardboard and colored with crayons. “We never had much money before, and we were always moving around. So my set was cheap and easier to pack.”

“Well, you have a permanent home now,” I assured her. So had her great-aunt Amelia and all of Winthrop’s descendants.

After a rootless childhood of tramping around the world with his scientist parents, Winthrop had been delighted to have a place that would always be his—or rather, ours—for as long as I chose to stay.

With the help of my pearls, we’d built this fancy lair over 140 years ago, and then I’d used more pearls to set up a trust fund that would maintain the house and grounds as well as provide generous allowances to the tenants like Winnie and her mother. Winnie should be able to buy any toy she wanted, so why was she still using a homemade one?

“Don’t you have the money to purchase a new set of checkers?” I asked. “Or perhaps your mother hasn’t had time to take you shopping?”

She began to set out the pieces, even though they slid about because she could not get the paper board to lie flat. “I told Mom this works just as well as a new one.”

In the corner of the board, I saw a W and an A inside a big heart. “I assume ‘W’ is Winnie, but who’s ‘A’?”

“Andrew, my dad,” she said, refusing to look at me.

I thought of a younger Winnie—hopefully with her hair actually brushed—coloring the pieces her father had cut from cardboard. “There are some things you can’t replace,” I observed.

“He was a real artist,” she said softly. But his death must have been a painful memory because she didn’t give me a chance to ask about him. “I’ll even let you go first,” she said brusquely. “You can be red.”

I had intended to lift her by the collar of her ragged T-shirt and toss her back out into the basement—and then wash my paws with strong soap—but instead, I sat down and used a claw to move my first piece.

“It’s funny that Amelia never told me that she was writing to you,” I said, trying to sound casual.

Winnie leaned over so all I could see was the top of her head as she shifted a piece to another square. “It didn’t matter where we had moved to, somehow her letters always reached us. Money, too, even though we never asked for it.”

That sounded like my sweet Fluffy. I fought the urge to cry because cleaning up the pearls can be such a nuisance. Humans have it so much easier when they weep. Still, my vision was a little blurry when I moved a piece.

“You just went two spaces,” Winnie said, “but I said I’d let you cheat today.”

“That’s quite generous of you,” I said sarcastically.

“I know how it feels when you lose someone you love,” Winnie said.

And I knew she meant her father. The strange little creature was trying to comfort me in her own clumsy way. It was just the sort of kind impulse that I had loved in Fluffy—though, of course, Fluffy would have been far more graceful doing it. But then, Fluffy had grown up in a world shaped by etiquette and with everything that money could buy, instead of moving around and having to make her own toys. But I was being disloyal to Fluffy’s memory, so I switched to other topics.

“You didn’t seem very surprised to see me in my true form for the first time,” I said as we went on playing. Fluffy hadn’t been either. And I had loved her all the more for that. In my experience, it’s a rare human who can accept you for who you truly are.

“I’ve always wanted to meet a real dragon,” she said. “My dad knew everything about them, so he was forever telling me stories about them.”

“He was an expert on dragons?” I asked. That would have made him very special among humans.

“Well, he was always reading about them,” she said, “and then making up stories.”

I almost slammed my paw on the board. “Do I look imaginary to you?”

“Of course not,” she said. “Who’d ever make up a dragon as grouchy as you?”

As she squinted at the board, studying her next move, her fingers rubbed against a silver medal hanging around her neck—it looked old-fashioned, embossed with a winged foot, the symbol of the god Mercury.

“Is that your good-luck charm?” I asked, trying to change the tone of the conversation.

“Yes,” she said. “My father gave it to me. His grandfather won it for the high jump. He was a fireman and the best athlete around.”

“Firefighters are noble folk,” I said, glad that her father had come from such stock.

“I know,” she said. “My dad always wore it to honor him, and now I do too … and it does bring me good luck.”

Suddenly she began to leapfrog a piece across the board to the end. “King me,” she said as she took away my pieces.

I stared down in dismay at the gap in the center of my defenses and a king ready to rampage in the rear of my lines. “I thought you said you were going to let me win today?”

She picked up one of the pieces I had taken and kinged her piece herself. “I said I’d let you cheat.” She grinned up at me. “But that doesn’t mean you’re going to win.”

I shifted in my chair, finding a more comfortable position while I figured out my next move. “You asked for it. Don’t cry when I rain down death and destruction on you.”

“Oh, I’m shaking in my boots,” she said mockingly.

As I studied the board, I couldn’t help grumbling, “You really ought to be scared of me, you know. I’m a dragon; I have teeth, I breathe fire. I could singe you to a crisp.”

She looke

d at me seriously. “I am afraid, but not because you might bite or burn me. I think you could do a lot more damage with your tongue than you would with your fangs and claws.”

I leaned my long neck to the side to study her from another angle. “Are you really only ten?”

She shrugged. “Mom says I’ve gone through a lot more than most ten-year-olds should.”

I thought about those words, maybe too much so, because she won not only that game but five more. Even Winthrop had never been able to win more than two games in a row from me—and I did not cheat him either!

“That’s enough cheering up for one day,” I said. “I can only take so much losing.”

She raised her arms over her head in victory and then rocked from side to side. “Great-Aunt Amelia wrote that you served her tea and cookies after a game.”

“Your great-aunt Amelia had better manners,” I sniffed.

Winnie lowered her arms. “You mean she let you win. Don’t be such a bad sport.”

“I’ll have you know that I won on my own,” I snapped. “And anyway, I ran out of tea this morning.”

Winnie couldn’t hide her disappointment. “Not even those little cookies shaped like flowers?”

“My cupboard is quite bare,” I insisted. I hadn’t felt much like shopping after I lost Fluffy.

“Well, it’s time for me to go anyway,” Winnie said, looking at the French timepiece on the marble mantel. “Mom’s still recovering from her fall. If I don’t watch her, she’ll forget to rest.”

I was thoughtful as she lifted the handmade board and poured the pieces into the box. “You take care of her, do you?”

“And she takes care of me. It’s always been me and her against the world.” She folded up the board and stored it away. “Sometimes she held down two jobs just so we’d have a place to live and something to eat. But now we got this house and plenty of money, so I can watch over you too.” When she stood up, Winnie fished a key from her pocket. “Want to add this one to your collection?”

“What would be the point,” I asked, “when you have all those other copies?”

“Maybe I lied yesterday.” She dangled the key between her fingers. “Maybe this is the only extra one.”

Winnie was more pest than pet. “Do you ever stop playing games?” I demanded.

“You may hate to lose, but I love to win,” she said as she left.

I stared at the door long after she had gone. I would have to take responsibility for her whether I wanted to or not. But I had raised enough pets to know that some of them needed to be challenged before they became bored and got into trouble—and I could see a creature like Winnie burning San Francisco down.

For Fluffy’s sake, I would see she got a good education at an extraordinary institution of learning like the Spriggs Academy—which might at least keep her from destroying the city.

CHAPTER THREE

Always make sure your pet knows who’s in charge.

The next morning, I disguised myself as a human and put my pearls into a large purse. Then I headed into my exit tunnel, leading under the lawn, away from the mansion, under several blocks, and up into a shed in a grove in a park. But when I reached the door at the end, it wouldn’t budge. Peeking from under the door was a pale scrap of paper. Though the tunnel was dark, it was no darker than the seafloor, where sunlight never reaches and dragons glide freely, so I had no trouble reading the scrawled message.

The note said:

ASK POLITELY AND I’LL UNLOCK THE PADLOCK ON THE OUTSIDE OF THIS DOOR.

WINNIE

A touch of spirit in a pet is one thing, but this was quite another. I crumpled up the note, angry at her insolence and even angrier at the threat to my freedom.

How dare she try to play tricks on me? I’d sneak out of the house and finish my shopping. When I came back, I’d snap the padlock from the exit door, and then teach Winnie not to trifle with a dragon.

As I stormed along my escape tunnel, I changed my revenge to a stern scolding. After all, the whole trip was for her sake. But when I stepped into my apartment, I found that another note had been slipped under my front door.

This one said:

CALL ME.

WINNIE

As if I’d let her tell me what to do.

With a snort, I tried to open the door and found it wouldn’t move either. She must have padlocked that door too. I had half a mind to smash the door to kindling, but I didn’t know how much Winnie’s mother knew about me. She might have heard the noise and come to investigate.

So instead, I picked up my smartphone. There was a note taped to it with a number.

I dialed, but she didn’t pick up until the ninth ring. “Hello, Miss Winnie’s residence.”

“Don’t you ‘Miss Winnie’ me,” I snapped. “Open my doors.”

“What’s the magic word?” she asked.

“You are overdue for a spanking,” I threatened.

“That’s more than one word,” she informed me, “and none of them are very magical.”

I caught myself just before I crushed the telephone into dust. The main thing was to get out of here quietly. “Please,” I said through gritted teeth.

“See how easy that was?” she asked cheerfully. “So where are we heading?”

“I have to buy some tea,” I said sternly, “and I will do so alone.”

“We’ll see,” she said slyly. “I’ll meet you by the exit door.”

It took her a half hour to open the door of my escape route and allow me to step out of the shed in the park. As I shouldered the purse’s strap, she stared at my upturned nose and short, bobbed blond hair. I was of an undetermined age, not too young, not too old … just in the prime of life.

I’ve taken on many human forms in my day, but for the past hundred years or so, I had usually modeled myself after a French girl I had met while traveling with my pet Orlando. Jeanne had been very sweet and made the most wonderful cheese until the day she fell from the loft in her family’s barn. Even though her bones had healed nicely under my care, she’d started hearing voices telling her to save France from the English. I’d always regretted that I hadn’t sat on her until the fit had passed because it had all ended very badly for her.

“I’m Miss Drake,” I said. “That’s an old word for ‘dragon.’ ”

“Not very inventive,” she sniffed.

“I don’t use the wrong name that way,” I said. “It’s easy to get confused when you’ve had as many identities as I’ve had.”

“Just how many fake identities have you had?” she asked curiously.

“As many as I’ve needed,” I said, and held out my gloved hand. “I’ll take that padlock.”

She passed the padlock to me, and I had the satisfaction of seeing her eyes widen as I crushed it in my hand. “Don’t ever lock me inside again. Now go home and open up the door to my quarters.”

“I promise,” she said. “Just as soon as we return from wherever we’re going.”

“I thought you said you had to keep an eye on your mother?” I asked her.

Winnie folded her arms and shrugged. “Mom’s getting some physical therapy. She told me to stay here because it would be boring.”

I sensed that Winnie was feeling a bit lonely in her new home. Perhaps a jaunt outside would do her some good. “You can come if you give me your word you’ll be quiet.”

She drew an invisible zipper across her mouth. “You won’t even notice I’m there.”

I doubted that. Winnie would always make her presence known. “How did you know where my exit door was?”

“Great-Aunt Amelia’s journal had a map,” Winnie said. “She put it in her last letter. She said it would help me get to know you.”

“Journal? What journal?” I demanded. It was news to me that Fluffy had been keeping one. “Your great-aunt never told me.”

“Maybe she wanted a little privacy,” Winnie said.

“Well, I wish you’d destroy that journal,” I said, and to

be sure she would do it, I added, “Please.”

“Not a chance.” She looked around the little grove of trees that grew around the shed at the center of the park. It sat upon the peak of a hill and was a square about a block on each side. All around us the lawn stretched down the slopes to the surrounding streets. “It’s amazing that no one ever found your door besides Great-Aunt Amelia.”

“There’s a charm that keeps people away,” I said, pointing to the yellow piece of paper with the spell that I had written in the special dragon script. It was also why this was the one spot in the park that was never littered with empty soda cans and potato chip bags. “Amelia knew about it only because I led her grandparents through it after the mansion collapsed in the Great Earthquake. Her father, Caleb, was only a young child then, and I carried him myself.”

“When did it fall down?” she asked.

“In 1906.” I waved a hand toward the eastern half of San Francisco. “We stayed here with a lot of other refugees, so we saw the fires start to burn what was left of the city. The smoke turned day into night, and there was a wall of flame slowly marching over the hills. I was just a whisker away from taking my true form and flying Caleb away. But the firemen, soldiers, and sailors fought the fires to a standstill and then put them out.”

As I stood on the hilltop, dragon-egg-blue sky all around me, I could feel the wings itch beneath the skin on my back, wanting to spread wide and fly.

When we left the park, Winnie asked, “Where are we going?”

“Shopping,” I said.

“But downtown’s that way,” she said, waving toward the east.

I set a brisk pace, hoping that she would have to save her breath for walking rather than talking. “What would I want with the bright trash they sell there? It’s fit only for”—I almost said “humans” but caught myself in time—“magpies. I take my custom to establishments that cater to creatures of more refined and elegant tastes.”

She drew her eyebrows together as if she were translating my sentences. “Are there really shops for dragons?”

The Tiger's Apprentice

The Tiger's Apprentice Bravo, Mia

Bravo, Mia STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord

STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord Isabelle in the City

Isabelle in the City Isabelle

Isabelle To the Stars, Isabelle

To the Stars, Isabelle Designs by Isabelle

Designs by Isabelle A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans

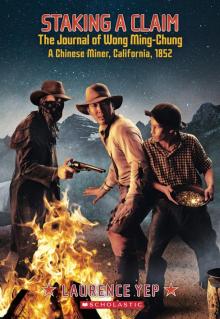

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Staking a Claim

Staking a Claim City of Ice

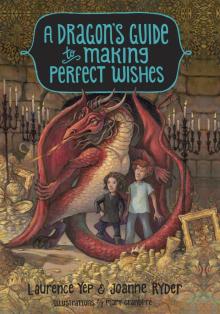

City of Ice A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes

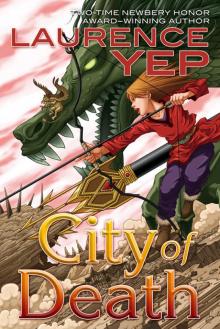

A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes City of Death

City of Death