- Home

- Laurence Yep

Staking a Claim Page 4

Staking a Claim Read online

Page 4

I can keep one small promise, though. With this letter you will receive the red silk ribbon for your hair. I bought it for you in the city.

I’m sorry that I can’t keep my other promises to you. I’ll make it up to you in some other life. For as sure as I am there is a heaven, I am also sure we will meet again.

I will miss everything about home. I will miss waking every morning and listening to you start the fire in the stove. I will miss tickling our daughter and hearing her laugh. I will miss the sight of the wind rippling through the rice fields. I will miss walking with you up to the cemetery to visit our oldest boy.

There was more about what to do after he died. At first, I didn’t want to put it down.

“You’re not going to die, a tough man like you,” I said.

“Here’s a little bug like you scooting around, and a big man like me is laid low,” he said. “Heaven must have a sense of humor.”

“I’m doing this letter, but you can give it to your wife yourself when you go home. Then you can both have a good laugh,” I said.

Sunny just smiled and went on.

At least Sunny owns three fields so his family could sell one of them to cover the debt.

When he was finished dictating, I signed his name and gave him the brush so he could make his mark.

He admired the letter. He hadn’t known he had said so many words.

I apologized for my handwriting. I’d been only average for my class.

Sunny didn’t care. He never thought he would see his thoughts down on paper like he was a scholar or an emperor or somebody important. He started to touch one of the words.

I warned him that the ink was still wet and might smudge. So he made a point of holding the letter by the edges as he gazed at it.

I have always enjoyed reading, but up until now I hadn’t enjoyed writing. I got whacked too many times by my teacher for that. I was always writing the strokes of a word in the wrong order.

Now, though, I see that writing has its own power. It was like magic to Sunny.

Sunny said his oldest boy would have been my age if he’d lived. They had buried him right underneath a pine tree.

Then suddenly he looked shy. He had one more big favor to ask. Of course I said I’d do it if I could.

He wants to be mentioned in my book. He added quickly that it doesn’t even have to be a whole sentence. Just his name.

Then he closed his eyes.

He only grunts when I try to encourage him. I wish I knew what to do. I’ve known him only a short while, but I feel like he’s an uncle.

June 13

Somewhere on the Pacific Ocean

We put Sunny’s body on the stairs. I feel like I will break inside. When will this trip ever end?

Even his ghost can’t go home because his body is at the bottom of the ocean.

My tears are smudging the ink. Soon I won’t be able to read this page. I have to stop.

June 17

Somewhere on the Pacific Ocean

We heard the thump of excited feet on the deck above. One of the sailors called down to us that we’ve made landfall.

Sunny almost reached the Golden Mountain.

I should be cheering like the others, but I have no laughter or smiles inside me.

Sunny is just another man who died trying to feed his family. There will be no record of his family’s grief when they get my letter. No one will know their tears.

But I will. And I will not forget.

June 18

San Francisco, or First City

The Golden Mountain is stranger, scarier, funnier, sadder, and more wonderful than I ever imagined. Now that I am here I will use only the American calendar.

When we got off the ship, I thought I was in the middle of a forest. Except I could hear the ocean. Then I realized the tall poles were the masts of ships. I was surrounded by hundreds of empty boats. They jam the harbor like fish in my village pond. I bet I could have walked from one deck to another across the bay.

I didn’t see any sailors. Instead, I saw laundry hanging from lines as if people were using the boats as houses. Then I saw one ship that literally had a house built on top of it. Maybe all the sailors had left their ships to find gold too.

Big, loud machines were pounding logs vertically into the mud a half kilometer from shore. Real houses perched on top of logs that had already been driven in. Men and machines were filling in the shoreline to make more space. In some places, they weren’t even bothering to move the ship, but were just filling the dirt around it. Blessing would have loved the machines.

First City nestles at the foot of steep hills between the shore and the hillsides. A few houses lie scattered on the slopes. Instead of building on the hills, they’re expanding into the water.

Though it’s summer, the air is as chilly here as winter back at home.

I have to stop now. They’re calling for us to register.

Later

Just got back. I don’t want to forget a thing, so I’m going to write it all down. But there’s so much.

After all these months at sea my legs are used to the motion of the waves. It was strange to stand on solid ground. My legs kept wanting to adjust for a moving platform. They still are.

On shore, there was a Chinese man shouting for people from the Four Districts to come over to him. Another was ordering Three Districts people to gather around him.

Gem, Melon, Squash-Nose, and I stuck together as a group. Our own district belongs to the area known as the Four Districts. We tried to ask the clerk what he wanted, but he looked impatient and bored. He snapped at us to wait and then went back to bawling out his call over and over.

When all the Chinese had left the ship, he mechanically began to recite a speech he must have given a hundred times.

It seems that the Chinese in the land of the Golden Mountain have grouped together by areas and family clans. But primarily by areas. His headquarters will act as our clearinghouse for everything — temporary shelter, jobs, and transportation to the gold fields. I was grateful to hear that.

The headquarters will also send our money and letters back home.

He emphasized that we will not be allowed to go home until we have paid back everything that we owe. If we die before then, they will see to it that our bones are shipped back for burial.

I felt a little trapped. It sounds as if the only way out of here is to die. But then I reminded myself that Uncle is doing well. He will watch over me.

Still later

Finally, real food! Rice, vegetables, and meat! At first, I wondered if I had lost track of time. Maybe it was a feast day. However, the people at the headquarters act like they have it all the time. At home only rich people can feast like this every day.

To get to Chinatown we had to pass through the American part of the city. San Francisco is like a big pot of stew with everything mixed in.

People seem to live in anything they can. In many places, I saw tents of dirty canvas. Other buildings were wooden fronts with canvas sides and roofs that flapped up and down. The first good wind ought to blow most of them away. When I asked the clerk, he explained that in the past three years, six fires had destroyed the city. The latest was just a year ago.

Then I saw some little cottages built out of iron. The clerk said that there used to be a lot more. However, in the last fire, many people had stayed inside them, thinking they were safe. Unfortunately, the flames turned the iron cottages into huge stoves. When the unlucky people tried to escape, they found the doors and windows had sealed tight and they were trapped. Most of them died.

Finally, we came to an area that the fire must have skipped. Tall buildings of brick or wood rose several stories high. Through the open windows and doorways came the sound of loud laughter. Gem tried to peek inside one place and got a hard-boiled egg in the face. He said they were gambling and drinking inside.

Other wooden buildings were so new that their lumber smelled of freshly planed wood and shone l

ike pale gold. Still others had already weathered gray while a few had been painted white, the color of death. At first I thought they were mausoleums for the dead. But as I passed I saw they were stores. All of them were crammed with goods. In fact, the goods spilled out of some them and were piled on the sidewalk.

Then I saw tall stone walls rising from the dirt. Chinese were on scaffolding building the walls, so I thought we were in Chinatown. However, when we just kept on walking, I asked the clerk.

He said it is an American building, but that tall mountains shut off this province from the rest of the country. It had been cheaper to bring the stones from China. Unfortunately, the assembly instructions had been written in Chinese, so the American owner had hired a boatload of Chinese stone masons to put it together. It is to be the First City’s first building of stone. I feel proud that it is Chinese who are doing that.

Have to go. Gem and Melon need help reading the employment notices.

Evening

San Francisco is also a big stew of people. Every country in the world has dumped someone into the pot. And most of us are hurrying to the Golden Mountain.

I’ve seen hair of almost every color, and faces and bodies stranger than the British man in Hong Kong. Many of them are Americans, but many others speak languages that don’t sound like English. They wear every type of costume from elegant to cheap and plain.

I also see people with skin the same color as mine. However, when I try to greet them, they don’t understand me. I don’t think they are speaking English, either.

Most of them are miners and look as eager and new as us.

The air is crackling with energy. I wish I could bottle it and sell it as a tonic.

Two things worry me, though. Even if the Golden Mountain is pure gold, can there really be enough for all the miners I see?

Almost all of them are armed with at least a pistol and a knife, too. Why do they need so much protection? And from what?

Could the Golden Mountain be even more dangerous than the sea voyage here? I don’t see how. And yet . . .

The others want to turn off the light so they can sleep. Another wonder. The light is inside glass. The Americans call it kerosene.

I don’t see how they can sleep. I know I won’t.

June 19

Another big meal. It was rice porridge and fried crullers like at home. But the porridge had big chunks of pork and preserved eggs. I’ve never eaten so well. Blessing would definitely have liked this part of the trip.

The Chinese live in an area on a steep hill of San Francisco. The clerk was careful to tell us the Chinese and American names in case we get lost. In Chinese, it’s the street of the people of T’ang. The T’ang was a famous dynasty back in China a thousand years ago. In English, it is called Sacramento Street.

However, since there are thousands of Chinese living here now, Chinatown has begun to spill over onto other streets, especially Dupont.

Like the American town, Chinatown is a mixture of wooden buildings and tents. The buildings are American-style but wooden carvings and signboards in Chinese mark their owners.

Above Chinatown, on an American street called Stockton, are a few wooden mansions where the richer Americans live.

Our group is luckier than some of the Chinese who have to stay in tents. We’re inside the headquarters itself. The smells make me feel right at home. Altar incense mixes with the smell of cooking.

We are crowded into a room on the second floor. Though we are packed side to side, it seems spacious after the Excalibur.

Later

Sad news. My three friends have decided to head for the southern mines. I tried to talk them into going to the northern ones where Uncle is. He’s at some place called Big Bend. But the clerk said the weather will be better in the south.

I will be alone again.

When it was my own turn with the clerk I had a bad scare. Naturally, Uncle had put my brother’s name on the forms and not mine.

That seemed to exasperate the clerk. (He was the same bored man who met us on the wharf and guided us here.)

At first, I was afraid I was going to be sent back. But somehow I straightened things out. When my business was done, I held out Sunny’s letter and asked him to send it to Two Streams. The clerk seized my hand instead. I got ready to punch him, but then he demanded to know how I’d gotten ink stains on my fingers. I told him I had been writing in my diary last night. It isn’t always easy to wash off the ink.

The clerk looked doubtful and insisted I take some dictation.

My parents have taught me not to show off. However, that stung my pride. So I took the brush. When I dipped the brush into the ink, it gave off this wonderful perfume. I could still see part of the picture of the carp on the side of the ink stick. It looked like ink a rich, important scholar would use.

Of course when I hesitated, the clerk thought that proved I was lying and couldn’t write. That made me nervous again and I told him I was just admiring the ink.

He took on a smug look then. In Chinatown, he got only the best. He was glad to see that I could appreciate it.

I noticed that the paper was good quality too. So was the brush.

When I asked him what he wanted me to write, he dictated a simple letter with basic words. It was easier than my teacher’s tests at home, which had hard, complicated words from the classics.

The clerk beamed when he looked at the dictation. I don’t know why. My writing is clear and legible but hardly elegant. My teacher always shook his head when he graded my handwriting.

Still later

The clerk came by to offer me a job!

So many Chinese come in every day that headquarters is buried in paperwork. That’s the literal truth. His little office was crammed with stacks of papers.

For a moment I was tempted. To live in the First City and see all of its wonders every day. To make my living by writing and reading. That all sounded like paradise.

Then I remembered my uncle. So I refused politely. But the clerk wouldn’t give up. He offered to write a letter. He said that if my uncle had any kindness in him, he would let me stay here.

I told him, though, that my uncle had sent for me to help him pick up the gold nuggets — the ones as big as melons.

He just sighed. When I learned my lesson — and if I survived — there would be a job waiting for me, he said.

I have this funny feeling in my stomach again. I have to admit it’s a bit odd. Why would anyone sit cooped up in a tiny office if there are such big nuggets to be scooped up? Maybe it won’t be as easy as Uncle told me.

When he left, I went down to the little altar in the headquarters. There were some incense sticks in a cup. I took out one of them and lit it from a candle. Then I set it in a cup of sand and said a prayer for Sunny.

I burned some incense for me, too.

June 20

Somewhere northeast of San Francisco

This morning I boarded a smaller boat by myself. It traveled across a broad bay and then through a series of smaller ones to a river.

The boat is crammed with miners traveling to the gold country. They clump together in groups, each of which talks a different language.

Because I couldn’t find water, I couldn’t write, so I got bored. There were some other Chinese on board, but they were busy gambling. They wouldn’t have allowed me to join even if I had had money.

So I wound up drifting over to the side of the boat to look at the water. Suddenly, a fish leapt out of the water. Its sides shone in the sun so it looked like a silver arrow. It was so lovely it would be a shame to eat it.

When the fish splashed back into the water, I felt a nudge in my side.

I spun around to defend myself. I saw an American boy with hair the color of fire. He looked to be about the age of Blessing. He grinned and pantomimed fishing.

I guess he had been thinking some of the same things.

Through signs, we learned each other’s names. It took a while to work out hi

s name because his name was in reverse. In China, your family name is the most important thing, so we put our family’s name first and our personal name second. Americans must think the opposite, because they put their personal names first and their family names last. Strange. His personal name is Brian. His family name is Mulhern.

He’s just as curious about me as I am about him. After a while, I forgot about how strange he looked.

Unfortunately signs got us only so far. So then he took out what I thought was a stick. It ended in a point with some black stuff. He called it a pencil.

He was able to write on the deck without a brush and ink. I don’t think I will ever give those up since the writing is nicer to look at, but the pencil is handier when you’re traveling.

Then, through pictures and signs, I learned that he is not an American. He comes from a country called Australia. I’m embarrassed to say that I have never heard of it. If I understand him right, his country is to the south of China.

I wish we had studied more about the world. However, our teacher felt that China was the most civilized country in the world. Why should we study any other place? We had learned about the Golden Mountain only because our clansmen were going there.

I admired his pencil so much that he gave it to me. I tried not to take it but he insisted. My new friend has a big heart.

I am writing this with my new writing implement. No more ink sticks. No more inkwells. No more finding water.

Later

I’ve already worn down the pencil. Brian showed me how to whittle the pencil with a knife to keep the point. I used it to draw him a crude picture of home, which I gave him as a present.

A boy with skin as dark as mine came over. Over his clothes he wore what looked like a black woolen blanket with a hole cut through the center for his head. Bright yellow, red, and blue stripes decorated the bottom.

Like Brian, he puts his family name last, but his personal name is Esteban and through our system we learned he is from Chile. Then a fourth boy joined us. He has hair the color of mud. His name is Hiram and he is a real American. Hiram and Brian speak different dialects of the same language. Hiram is a year older than Brian. Esteban is about a year younger.

The Tiger's Apprentice

The Tiger's Apprentice Bravo, Mia

Bravo, Mia STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord

STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord Isabelle in the City

Isabelle in the City Isabelle

Isabelle To the Stars, Isabelle

To the Stars, Isabelle Designs by Isabelle

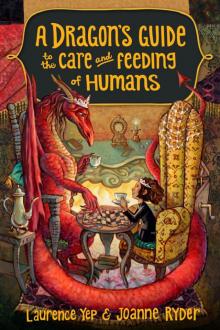

Designs by Isabelle A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Staking a Claim

Staking a Claim City of Ice

City of Ice A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes

A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes City of Death

City of Death