- Home

- Laurence Yep

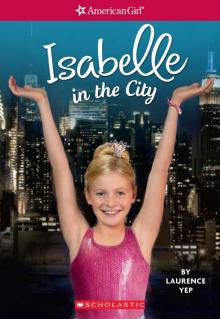

Isabelle in the City Page 5

Isabelle in the City Read online

Page 5

Miki was busy fingering the packing paper, a worried expression on her face. “It has wrinkles,” she said. “We need something to roll over it.”

“A rolling pin?” I suggested. I had seen one in the kitchenette when we’d gotten our water and flour there.

It took a while for Miki to figure out what I was talking about, but when she did, she shook her head. “Something bigger,” she said.

Anneke piped up with an idea. “The prop department usually has wooden dowels,” she said, holding out her hands to show Miki about how long the dowels might be.

Miki nodded. “Yes, good,” she said.

Abby deposited her paper by our door. “Let’s go check right now,” she said, motioning to the other two girls.

They returned a half hour later carrying a dozen dowels of different lengths, from about a foot and a half to two feet long. Abby held one of them as if she were saluting with a sword. “How are these?”

“Very good,” Miki said, her eyes bright.

After Abby and her friends left, Miki cleared off her desktop, laid out a sheet of brown paper, and reached for a dowel. She put as much weight onto it as she could, the muscles on her arms standing out. She slowly rolled over every inch of the paper, repeating the process several times. When she was done, she had managed to smooth out the paper, and the wrinkles looked like nothing more than a marbled pattern.

Miki smiled a satisfied smile and stood to stretch out her arms. “Now I will try to fold it,” she said.

I sat down on my bed so that I could watch the paper artist experiment.

At first, all Miki did was study the paper from both sides and all angles. After a while, she cut the bottom of a long sheet of packing paper into halves that she twisted and then shaped into feet. I loved watching her hands work.

Next, she cut the other end of the sheet into three strips. The middle one was very thick, while the two narrower ones became arms and hands. The edge of the middle strip was cut into thinner strips that would become branch-like hair, and the lower portion became the head.

Finally her fingers began to fold and tuck the middle part of the sheet into a torso. She put some wrinkles back into the lower part of the torso to form a pleated tutu.

When Miki was done, I felt like clapping. She had made a single sheet of packing paper rise into a three-dimensional dancer. But Miki wasn’t satisfied yet. She went through four more sheets of paper until she made a dancer that she was happy with. Then she sat back on her bed and smiled at me.

After dinner, everyone on our floor met by the elevators. Miki used putty to hang her dancer on the wall as a sample for everyone to see.

Then Miki showed the girls how to cut the paper and how to fold and pinch each face so that it would have a nose, eyes, and mouth. I’d already seen how nimble her fingers were, but the others murmured in amazement as she made arms, fingers, hair, and legs. Finally, she showed them how to make costumes for their dancers.

Soon the air was filled with the sounds of snipping scissors and rustling paper. Miki became really popular as girls kept asking her to show them how to do something again or to check what they had done themselves.

Despite Miki’s efforts, I could see that some of the ballerinas were going to look better than others. But no one seemed to mind. Every now and then, one of the girls would get up to model a dance move for the paper version of herself. Our floor mates were feeling creative and having fun.

Even though I’d never made one of the ballerinas myself, Jade and Abby drafted me as their personal coach.

For one of their dancers, Jade used Abby’s phone to take several pictures of Abby in fifth position, with her legs crossed and the heel of her forward foot touching the toe of her back foot. Her arms were raised over her head, elbows slightly bent, fingers pointing toward one another.

Jade was just going to have Abby take her picture in first position, but I couldn’t help meddling. “Jade, you really look good when you do this move.” I rose on my left foot and kicked my right leg up. I didn’t get it beyond my shoulder.

“You mean like this?” Jade kicked, and her leg kept rising and rising until her foot was above her head. She looked so strong, flexible, and beautiful when she did that.

Abby quickly took a photo. “Nice, nice. Let’s take a couple more.”

When she and Jade were done, the three of us sat down and began to work on their ballerinas. Kayti, Emma, Betje, and Piera were right next to us as they worked on their dancers, too.

“Abby, when you finish high school, are you going to apply to college or to a ballet company?” Emma asked as she tried to shape the arm of her dancer.

“I thought I’d try to join New York City Ballet,” Abby said. “You all should, too.”

Piera shook her head. “I want to stay in Europe at least—maybe the Paris Opera Ballet.”

“It’s Oz for me,” Kayti said. She stuck her tongue out of the corner of her mouth as she folded her paper into the pleats of a tutu.

“Oz?” I asked, puzzled.

Abby laughed. “Kayti isn’t jumping into a Kansas cyclone,” she explained. “Oz is slang for Australia.” She motioned to Jade and me. “So, what company would either of you like to get into?”

I laughed. “I’m just glad to be here right now,” I admitted.

“I just want to go someplace where I can keep dancing,” Jade said.

“Well, a lot of companies have internships or preprofessional programs,” Abby said. She obviously had done her homework, because she began to tell Jade about some of those programs. Then she added, “But think about NYCB, Jade. If we both get in, maybe we could room together.”

“Me?” Jade asked, surprised.

“You don’t want to?” Abby asked. “I think we get along really well. You’re as serious about your ballet as I am about mine.”

Jade’s cheeks flushed, and I could see how happy she was, surrounded by her new friends. As we worked, she relaxed more and more. This smiling, laughing Jade was more like the sister I know from home. All she had needed was something—or someone—to break the ice. By asking for her to help me with the paper project, maybe I had actually helped her a little, too.

When the dancers were complete, Miki and I helped our floor mates design costumes that each looked a little bit different. Miki showed the other girls how to adjust the paper clothing with skillful pulls and folds, sometimes adding more paper for sleeves. Then Jade and I helped to bring those costumes to life with ribbon and sequins. We used up Mom’s gift, but Jade and I agreed that we would get her something else when we shopped for Dad.

Once we had put the finishing touches on the last ballerina, all the girls went around to see one another’s doors. We stood out in the hallways, laughing and chatting—excited to share this moment together.

And that gave me another idea. I got some tape and construction paper from our room and cut out some letters. Then I put them up over the doors in our hall. Together, the letters spelled: “SHARE THE DANCE, SHARE THE FUN, SHARE THE FRIENDSHIP.”

Between dance classes and designing doors for the contest, I thought I’d be too tired to be nervous when the judges finally began visiting the floors. But I felt kind of twitchy as I waited for the decision in Jade’s room with Miki, Abby, Piera, and Kayti.

All the girls were so excited that they talked louder than usual, but I found myself just staring out the window. New York looked so pretty at night, the lights like strings of shining pearls and the river like a silver ribbon under the moon.

Suddenly an arm wrapped around my shoulders. “Don’t look so worried, Isabelle,” Abby said. “We did the best we could.”

Piera shrugged. “Who knows what the judges will like?”

“Well, I think the doors on our floor are the best,” said Kayti. She held up her can of soda as a toast. “So cheers. Here’s to Isabelle, Miki, and Jade. They did a super job.”

I raised my soda. “Here’s to everyone. We all did great.” No matter who won the c

ontest, I felt as if I’d won the best prize—their friendship.

Suddenly someone knocked at the door. “Come in,” Jade called.

When the door opened, it was Hailey. “I just wanted to congratulate the winners,” she said with a broad smile.

Abby gave a whoop. “Winners? You mean our floor won?”

Hailey nodded. “Come out by the elevators, girls.”

The identity of the judges had been kept secret, but when all our floor mates had gathered by the elevators, we found Ms. Aloff, Ms. Harris, and Ms. Pujol waiting there for us.

“Thank you, girls,” said Ms. Aloff. “I was so touched by your floor design and theme.”

“She almost cried,” Ms. Harris told us with a laugh, and pantomimed tears rolling down her own face.

“I’ve taught a lot of fine dancers over the years, and this year is no exception,” Ms. Aloff said, “but I’ve never seen a dorm floor work so hard together—and so beautifully, too.”

As Ms. Aloff went on with her speech, Ms. Pujol leaned over and whispered to me, “I hear a lot of this was your idea.”

“It was everyone’s,” I said.

“And the costumes for the dancers on each door?” Ms. Pujol asked.

“Well, those were Miki’s and my idea.”

“Well, you both have an eye for fashion,” Ms. Pujol said.

“Thank you, ma’am,” I answered proudly.

Even after the judges and Hailey had left, my floor mates and I stayed together in the hallway. We’d worked hard, so winning felt extra special.

My dad is a musician, and when he’s happy, he likes to play his drums. And I guess a singer sings. But I am a dancer, so I had to dance. I began to wriggle my head and roll it in circles.

Miki caught on right away, and her whole body began to sway.

I threw up my hands. “Best floor, best floor,” I said, stamping my feet to each beat. Miki did the same, drumming her feet on the floor with each cry.

With a whoop, Jade began to circle around us, stamping and chanting “Best floor” at the same time. Kayti and Betje joined in, too. And then so did all the others.

The good feeling from that night stayed with me the whole next week, so I danced better than ever in my classes. And that feeling only got stronger on Saturday when I boarded the bus with Jade, Miki, and all my friends from the floor and our chaperones. The drive from New York to Saratoga was a long one, but we spent the whole time laughing, singing, and joking around together.

After a few hours, we reached our destination. The Saratoga Performing Arts Center sat on the edge of a vast lawn, looking like a double-layer cake on a green felt table. People were picnicking on the grass, waiting to go to their seats.

As we got in line for pizza from one of the food stands, I suddenly felt a little homesick.

“Back home, we’d probably be getting lunch at the flea market and listening to Dad’s band,” I said to Jade. “I wonder what Mom and Dad are doing today.”

“Missing us, of course,” Jade said.

Miki was right behind us. “What do your parents do on weekends, Miki?” I asked.

“They sometimes go to festivals at a shrine. At night, there are fireworks,” she said, spreading her arms. “They look like big, big flowers.”

We all were a little quiet as we thought of home. But when our group finally got to go up the ramp to the balcony and we took our seats in the center, I was so excited that I sat on the edge of the cushion. I love home, but I love dancing just as much. I guess I’ll always be pulled both ways like this.

The first piece performed by New York City Ballet was Emeralds. It had been choreographed by one of NYCB’s founders, George Balanchine, whom I’d read and heard so much about.

As the performers danced across the stage in their emerald costumes, they reminded me of leaves drifting through the air. It felt so hard to sit still! I wanted to get up and float like a leaf, too, spinning gracefully above a riverbank. As the dancers swirled together, they fused into one—like the green flickers of a fire. I couldn’t look away.

Just as I was catching my breath from that awesome spectacle, the music began for West Side Story Suite. The dancers’ movements were so strong, sleek, and powerful! I wanted to get up and prowl like a panther, too.

When the rest of the performance was over, my friends and I lingered in our seats, talking excitedly about what we’d seen. We were one of the last groups to leave the center, and as we were walking back down the nearly empty ramp, I saw the green lawn in front of me. It seemed like the biggest stage ever, and I couldn’t hold back any longer. I just had to run.

Jade raced to catch up with me. “Hey, where do you think you’re going?”

But I couldn’t answer with words. I sprang and whirled across the grass.

Miki was right next to me. She understood what I was feeling without my having to tell her. Spreading her feet wide and throwing back her head, she held out her hand and struck a pose in a silent invitation to dance.

I accepted by throwing both my hands into the air and spinning around like a top.

Together we danced across the grass. And when we jumped into the air, I tried to explode like Miki’s fireworks—big, bright, and beautiful.

Suddenly, I felt a hand grab mine. I turned to see Jade grinning at me. Abby had Jade’s other hand, and the rest of our floor mates were running up to form a chain. I grabbed Miki’s hand, and we danced in a long line that snaked back and forth across the grass while our chaperones laughed and clapped.

We all had come from so many different places, and some of us spoke different languages to our families and friends. But as I’d learned with Miki, we could all speak “dance” to one another.

I caught Miki’s eye and smiled at her. For just a moment, she freed her hand. Then she clasped both hands under her chin, and I recognized the word immediately.

It was the dancer’s sign for happiness.

Laurence Yep is the author of more than 6o books. His numerous awards include two Newbery Honors and the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal for his contribution to children’s literature. Several of his plays have been produced in New York, Washington, D.C., and California.

Though The Nutcracker was a regular holiday treat for Laurence as a boy, it was his wife, Joanne Ryder, who really showed him how captivating and inspiring dance can be with her gift of tickets to the San Francisco Ballet. Their seats were high in the balcony, yet they were able to see the graceful, expressive movements of the dancers far below.

Laurence Yep’s books about Isabelle are his latest ones about ballet and a girl’s yearning to develop her talents and become the dancer she so wishes to be.

Special thanks to Shannon Gallagher, owner and instructor at Premier Dance Academy, LLC, Madison, WI; and to New York City Ballet: Peter Martins, Ballet Master in Chief; Katherine Brown, Executive Director; Robert Daniels, Managing Director of Communications and Special Projects; and Karen Girty, Senior Director, Marketing and Media

Dowel (dowl): A wooden rod that can be rolled over paper to smooth out the wrinkles before folding

Origami (or-ah-GAH-mee): The Japanese art of folding paper into decorative shapes and figures

Papier haute couture (pah-pee-AY oat koo-TURE): The designing and making of high-quality fashionable clothes out of paper

Papier-mâché (pay-per-mah-SHAY): A substance made from the pulp of paper (and sometimes flour and water, or glue) that can be molded when wet and painted when dry

Washi (wah-shee): The Japanese word for traditional papers made from the fibers of three plants. Wa means “Japanese,” and shi means “paper.”

Wet-folding: An origami technique that uses water to dampen paper so that it can be folded more easily and takes on a more rounded, sculpted look

Akira Yoshizawa (AH-kee-rah yo-shee-zah-wah): A Japanese origamist who was considered the grandmaster of origami and who developed the wet-folding technique

For Isabelle, making dresses from paper is a fun new fashion

technique. But as she discovers during her tour at the Fashion Institute of Technology, paper dresses have had a long history. They first hit the U.S. market in 1966, when the Scott Paper Company designed them as an advertisement. If customers sent in $1.25, they could receive a dress made of paper, along with coupons for Scott products.

A paper-fashion craze soon followed. By 1967, paper dresses were sold in major department stores—usually for less than $10 apiece. Other clothing was made from paper, too, such as raincoats, bathing suits, and even bridal gowns.

Unfortunately, paper clothing had its downsides: it often didn’t fit well, was uncomfortable, and too quickly ended up in the wastebasket. By the late 1960s, paper clothing had all but disappeared. But the paper dresses of the 1960s continued to inspire fashion designers.

In 2003, Japanese designer Yumi Katsura presented dresses made of Japanese washi paper as part of her Paris collection. The paper she used was from the Echizen region of Japan, where washi paper has been made by hand for almost 1,500 years. Her designs combined traditional Japanese style and paper-making skills with contemporary fashion.

Today, paper fashions still appear at design shows and contests all over the world. Perhaps Isabelle will design one someday, inspired by the paper art of her friend Miki!

Meet the 2017 Girl of the Year, Gabriela McBride! She’s a true talent who gets creative for a cause.

Can Gabby use the power of her poetry to save her beloved community arts center from shutting down?

Turn the page to read a preview of Gabriela’s first book!

Toe-heel-toe-heel-toe-heel-STOMP.

Toe-heel-toe-heel-toe-heel-STOMP.

Each move burst into my head like a shout. All around me the air was filled with the sounds of tap shoes scraping and stomping, Mama calling out the next step as she snapped in time to the rhythm of the music. Above me, the sun poured through Liberty’s stained-glass windows, leaving little pools of colored light on the floor at my feet.

The Tiger's Apprentice

The Tiger's Apprentice Bravo, Mia

Bravo, Mia STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord

STAR TREK: TOS #22 - Shadow Lord Isabelle in the City

Isabelle in the City Isabelle

Isabelle To the Stars, Isabelle

To the Stars, Isabelle Designs by Isabelle

Designs by Isabelle A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans

A Dragon's Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans Staking a Claim

Staking a Claim City of Ice

City of Ice A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes

A Dragon's Guide to Making Perfect Wishes City of Death

City of Death